On Memorial Day, the Hero's Journey, Trauma, and 'Being With' Confusion

I began writing this piece at the beginning of 2024, but then I got distracted when my computer got stolen. As it happens, I picked this up again months later, on the weekend leading up to Memorial Day in the “United” States. The timing struck me. Upon a cursory Google search, this is what I find about Memorial Day:

What is Memorial Day?

The holiday takes place annually on the last Monday in May and is a dedicated day for honoring U.S. military personnel who have died while serving in the United States armed forces.

Over 1.3 Million Americans have paid the ultimate sacrifice for their nation.

But the first text you encounter on this page (nbcdfw.com) reads:

In recent history, Memorial Day has meant the unofficial start to summer. Families BBQ on the grill, the local pool announces its opening day, and retailers promote big sales.

Is anyone mourning today? Likely, those who’ve lost a family member. Perhaps those who have done a bout of military service and returned. But what are we collectively honoring? How is it that a holiday, founded to mourn soldiers who died in the midst of the American Civil War (can I just say that again? the American Civil War. I hear we might be due for a sequel), now means barbecues and the promotion of big sales?

I don’t have an answer, but I wonder if you’ll take a little walk with me.

For many years I was on a crusade to deconstruct the legacy of a book called King, Warrior, Magician, Lover (KWML). This book was aimed at men, and at the time I read it, I found it quite compelling. It had a huge impact on a generation of men, and that impact continues to this day in the modern “men’s work” sphere, where you shouldn’t be surprised to hear some guy in his 30’s or 40’s waxing mythopoetic about what it means to be a King, without any real context for where the word comes from, or what a king in the ancient world actually represented.

As my perspectives on masculinity and my exploration of archetypes in relation to masculinity have developed, I’ve grown to feel KWML dutifully carries the legacy of patriarchy into the future, all the while riding a cultural wave which seemed interested in cultivating something in the heart of the masculine that was deeper, more soulful, and less naive about the overculture’s scripts for men. It’s not that KWML gets everything wrong, but rather it mixes some interesting perspectives with many toxic tropes of masculinity. The truth therein makes the lie all the more insidious. At its strongest, it argues for balance and maturity. But the systematic, totalizing mode of its delivery sets it up to appear as if it has the answer to what it is to “be a man”. In this way it falls prey to the grandiosity its very pages warn against.

My contention focused primarily on the archetype of the Warrior as presented in KWML, and later extended to perhaps the most popular piece of mythic vocabulary in our culture, coined by Joseph Campbell: the Hero’s Journey. Campbell’s phrase was a crystallization of an aptly heroic exploration of world mythologies. All that is needed is a cursory read of his work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, to see the breadth he was intending to cover, the depth he hoped to reach.

The attempt, however well-intentioned, to make the world’s many mythic territories approachable to westerners ends up, in our culture, reducing the mythic journey he describes to 1) a man’s journey and 2) the journey of an exceptional man, wherein he must learn to fight in order to defeat some great monster or enemy. I believe this reduction to be a function of a certain cultural gravity already present in the West. Namely, we’re a bit obsessed with warring and conquering.

One of the decent ideas KWML presents offers another reason why the Hero’s Journey is such a popular and dominant narrative, one that's a bit more compelling. It posits that the Hero is an adolescent expression of the more adult Warrior. The idea being that we need the naive leap-now-look-later energy of the Hero to break out of a state of immaturity into a higher tier of development. This tracks with Campbell’s analysis of the Hero’s Journey as an essentially initiatory process.

So if the Hero’s Journey depicts an initiatory experience young men need to receive, the ubiquity of stories about the Hero might speak to a need in adolescent men for initiation which is not occurring. Observing the immense popularity of superhero films in the recent decades, with a preponderance of male viewers, we might wonder if these films (and their associated source material) are so popular because they speak to an underlying need for initiation that is going unfulfilled.

I learned recently, though, that Campbell based some of his work on the work of a renowned historian of religion and philosopher that preceded him, named Mircea Eliade. Eliade had a different name for the arc which Campbell called the Hero’s Journey. He called it the Medicine Journey.

Eliade’s Medicine Journey is structured quite simply. One begins in the village, or the known world. They then journey into the unknown, motivated by some need that exists within the village. Their journey may take place in an unfamiliar land, or some other kind of territory, such as an inner landscape, but the journey, by its nature, will require them to stretch beyond themselves. They will encounter a threat which brings their life into question. If they are successful, they will return with something vital for the village. Perhaps it is literal medicine, but the fact might be that it is their transformed self, their newly acquired capability, their ability to confront fear, which is the true medicine.

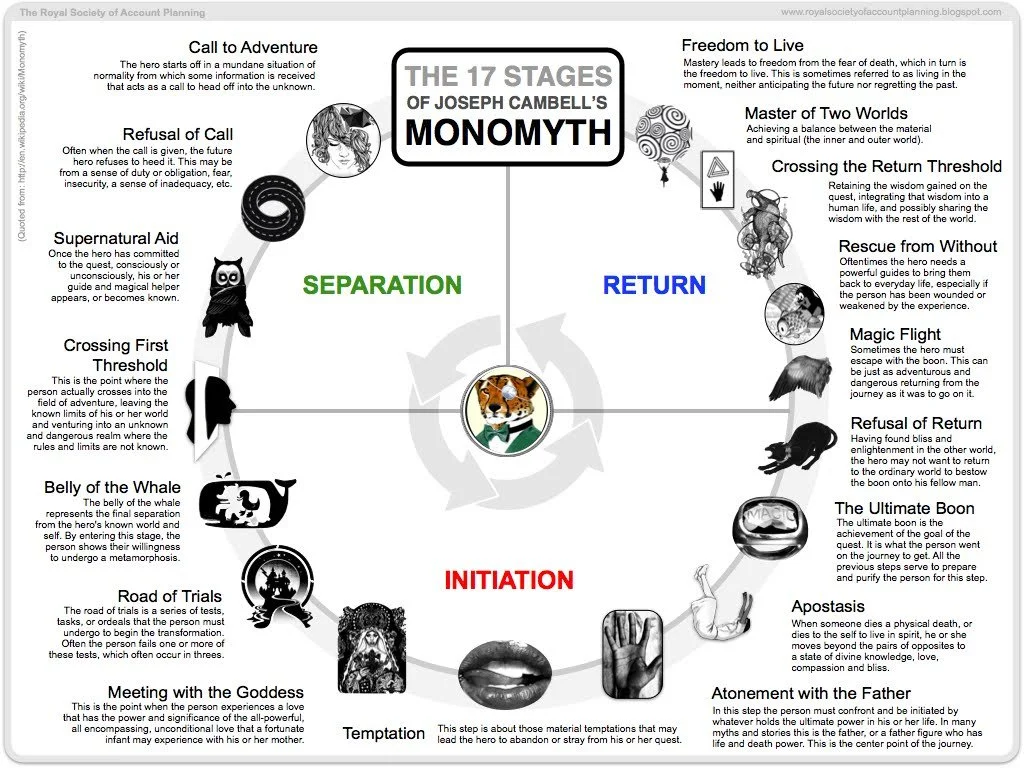

Campbell uses this foundation and elaborates on it to construct his more complicated version, including such phases of the journey as “the belly of the whale,” “meeting with the goddess,” and “atonement with the father.” One other primary feature of Campbell’s rendering is the use of the term “monomyth” to describe the Hero’s Journey. By looking at this appellation of “monomyth” and the characterization of the protagonist of this journey as a “Hero” we can start to see the ways Campbell was distorting something more fundamental.

Why must the one who goes on a journey to bring back medicine be characterized as a Hero, with all the associations of masculinity and warriorship that that word carries?

Does the exceptionalism of the Hero being cast particularly in the realm of combat not create undue emphasis on fighting ability, when an individual’s contribution to the village may lie in an area altogether unrelated?

And might the idea of the monomyth slide a bit too easily into the framework we’ve inherited as westerners, a framework that wants to package things in terms of individual acheivement and achieving the peak of hierarchy, deprioritizing the intelligence of ecological diversity which supports resilience?

These are the sort of questions I’ve been asking.

I contend that our culture still lives in the shadow of the Warrior; and more specifically, our culture lives in the shadow of the Soldier. Some of the relevant values I’ve come to associate with this mythic milieu:

a glorification of a battle-oriented mentality (rather than a musical, ecological, or relational mentality),

adherence to codes of conduct that breed conformity (rather than valuing the process of experimental trial and error), and

high priority placed on the ability to detach from emotion and sensation in order to overcome what appears threatening.

This starts to get interesting for me as I learn about trauma, and reckon with the nature of initiation. The qualities listed above all stand in stark contrast to the understanding I’m slowly developing of how trauma is resolved.

One way the traumatized nervous system deals with its excessive charge, is to charge right into the eye of a storm of intensity, believing it can resolve its trauma in this way. This strategy isn’t entirely wrong. By recreating or being drawn to similarly charged circumstances as when a trauma occurred, the nervous system gets an opportunity to have a different experience. It's getting a chance to resolve that trauma by finding a different way through the experience. But what tends to happen is a reiteration of the initial trauma. Without a shift in the nervous system, a reorientation that allows for a higher degree of presence, the pattern merely repeats and is reinforced.

(photo by Nsey Benajah, IG)

An alternative strategy of dealing with trauma entails avoidance of circumstances that might trigger the latent charge. Preordained pathways are determined to eliminate variability and avoid triggers. This looks quite similar to a code of conduct or script. This “do as you’re told” approach operates both implicitly and explicitly. We need look no further than the trope “boys don’t cry” for an example of an explicit code of conduct. Implicit codes of conduct might include the ambiguity associated with the fear straight men have of being perceived as gay. This prevents sharing of feelings, expressing joy, an openness to physical support, or even a heartfelt hug. And beyond this, it stunts a willingness to play and create. The shame with which men have been conditioned, when one steps out of line, creates an invisible electric fence that keeps them within certain societal parameters that do not actually serve a thriving individual, within a thriving village, within a thriving ecosystem.

One other sure sign of trauma is a high degree of dissociation from emotion and physical sensation. This detachment from the body does great service to a social system that at one point prized a willingness to do violence in men. Now the dissociation goes a long way in keeping men focused more on receiving external validation, rather than a felt sense of inner satisfaction. It allows them to push their physical limits and ignore their health in pursuit of a paycheck. And it keeps them separate from other men, not to mention every other feeling human being that surrounds them.

Yet, the whole purpose of the Hero’s Journey is initiation. Something has been stunted. These qualities which have a high degree of correlation with western standards of “straight” masculinity, directly oppose what is needed in order to come back from an initiatory experience–to actually return from the Hero’s Journey.

Initiatory practices in other cultures are easily seen from a western lens as “traumatic”, but what needs to be very clear is that trauma is not about what happens. It's about how it is processed, and made sense of. The qualities above describe a clear formula for preventing integration after an impactful event, which might leave an individual traumatized. What is clear though, is that initiatory experience requires a felt sense of mortal threat. We need to feel as if we might die (on some level), in order for the reordering of our being to be enacted.

At some point in my bone-picking, cud-chewing, and navel-gazing about the Warrior and the Hero’s Journey I got curious about the etymology of the word Warrior. The Proto-Indo-European root of the word “war” turns out to be “wers-”, which means “to confuse, mix up”. Now, this did quite a lot for me. It removed the overly gendered association with men and broadened the definition beyond mere battle and fighting. From this etymological deep dive, I rendered something like “one who contends with confusion” as an alternative frame for the Warrior.

Well, some months ago I was participating in a training for a healing modality that works with trauma, called Somatic Experiencing. We were learning about something referred to as “coupling dynamics.” Without getting into the weeds and intricacies of the modality, something striking was spoken in this context by our teacher, Joshua Sylvae. He said, “often one of the most provocative things we can ask of our clients is to go right to the center of their confusion and stay there.”

I had been making notes during the lecture, writing words and phrases he had been using to articulate this feeling of confusion in the nervous system, and translating them into mythic language. Phrases like underworld, the churning ocean, the abyss, the unknown land, and the belly of the whale filled the page. He described how the traumatized nervous system experiences confusion as an existential threat, but when the client can sit long enough with this feeling a dramatic “coming together” occurs that creates a profoundly positive experience in the body. Parts of experience which had been dissociated come back into the wholeness of being. Essential aliveness flows through the body.

Campbell uses the word “elixir” to describe what is attained in the moment of transformation when death is confronted at the nadir of the Hero’s Journey. Without reducing what is being spoken of in the Hero’s Journey to one thing in particular, I found myself relating this “coming together” after trauma, as an embodied version of gaining the elixir–an unveiling of capacity, which has more a quality of “staying with” confusion, than of “fighting off” a monster.

In Mircea Eliade’s work he acknowledges a trajectory in many myths toward a reconciliation of opposites which have sprung from a common source. He refers to this as the coincidentia oppositorum, or the coincidence of opposites. Ultimately, the Hero’s Journey evokes this encounter of opposites. The heroic man confronts the monster, which is all too often characterized as female. The Hero often acquires something from this encounter which he brings back, but again, this characterization models a conflictual ethos, not a reconciliation

This narrativized and glorified modeling around conflict, I believe, funnels us toward particular patterns of relating. It predisposes us to see an enemy, rather than mystery. It predisposes us to take action, whether fight or flight, rather than stand in wonder at what is before us, in hopes that it might reveal some extraordinary truth.

The coincidentia oppositorum, in Daniel Deardorff’s words, means to “hold contraries in creative tension without dropping, devaluing, or denying one over the other.” Can you imagine a world shaped by that myth?

It seems evident that this was why Memorial Day was actually founded. Two sides rose in conflict out of a greater oneness. And their common humanity, their shared grief over what had been lost, was in theory given space for expression.

This kind of space, the space to sit with and marvel at the horror and the wonder, is, according to Joseph Campbell, at the root of our most ancient mythic and ritual way of being in the world:

Traditionally, the first function of a living mythology is to reconcile consciousness to the preconditions of its own existence; that is to say, to the nature of life.

Now, life lives on life. Its first law is, now I’ll eat you, now you eat me—quite something for consciousness to assimilate. This business of life living on life – on death – had been in process for billions of years before eyes opened and became aware of what was going on out there, long before Homosapiens’s appearance in the universe. The organs of life had evolved to depend on the death of others for their existence. These organs have impulses of which your consciousness isn't even aware; when it becomes aware of them, you may become scared that this eat-or-be-eaten horror is what you are.

The impact of this horror on a sensitive consciousness is terrific – this monster which is life. Life is a horrendous presence, and you wouldn't be here if it weren't for that. The first function of a mythological order has been to reconcile consciousness to this fact.

The first, primitive orders of mythology are affirmative: they embrace life on its own terms.

The only way to affirm life is to affirm it to the root, to the rotten, horrendous base.

That's the first function of mythology: not merely a reconciliation of consciousness to the pre-conditions of its own existence, but reconciliation with gratitude, with love, with recognition of the sweetness. Through the bitterness in pain, the primary experience at the core of life is a sweet, wonderful thing. This affirmative view comes pouring in on one through these terrific rites and myths.

How do warring sides recognize the original source from which they were birthed? What rituals of reconciliation might we revive and enact to find ourselves again in relationship with those who we’ve become polarized from on personally, and collectively?

Again, I don’t have an answer. But one response I have from this little walk we’ve taken, is to see if I might find myself in contact with some former soldiers, perhaps doing trauma work, perhaps just listening. That might be a way to make some beauty, a way to honor the story they were telling. Maybe I’ll meet a hero. If you’re reading this and have a lead, let me know.

In Grace, Rainer Moon Raven